Ladakh Travel Guide

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Ladakh Home » About Ladakh Travel Guide » Religion & Culture » Historical Background » Ancient Routes » Modern Routes

Central Ladakh » Fairs & Festivals » Oracles & Astrologers » Arts & Crafts » Cultural Tourism » Archery & Polo » Adventure in Ladakh

The New Areas » Tourist Information » Air Line Ticketing » Car Coach Rentals In Ladakh

Travel Agents & Tour Operators in Ladakh » Hotels & Resorts in Ladakh » Map »Travellers Tools

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Ladakh Home » About Ladakh Travel Guide » Religion & Culture » Historical Background » Ancient Routes » Modern Routes

Central Ladakh » Fairs & Festivals » Oracles & Astrologers » Arts & Crafts » Cultural Tourism » Archery & Polo » Adventure in Ladakh

The New Areas » Tourist Information » Air Line Ticketing » Car Coach Rentals In Ladakh

Travel Agents & Tour Operators in Ladakh » Hotels & Resorts in Ladakh » Map »Travellers Tools

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Religion & Culture

The

traveller from India will look in vain for similarities between the land and

people he has left and those he encounters inLadakh. The faces and physique

of the Ladakhis, and the clothes they wear, are more akin to those of Tibet

and Central Asia than of India. The original population may have been Dards,

an Indo-Aryan race from down the Indus. But immigration fromTibet, perhaps

a millennium or so ago, largely overwhelmed the culture of the Dards and obliterated

their racial characteristics. In eastern and central Ladakh, today's population

seems to be mostly of Tibetan origin. Further west, in and arond Kargil, there

ismuch in the people's appearance that suggests a mixed origin. The exception

to this generalizationis the Arghons, a community of Muslims in Leh, the descendants

of marriages between local women and Kashmiri or Central Asian merchants.

The

traveller from India will look in vain for similarities between the land and

people he has left and those he encounters inLadakh. The faces and physique

of the Ladakhis, and the clothes they wear, are more akin to those of Tibet

and Central Asia than of India. The original population may have been Dards,

an Indo-Aryan race from down the Indus. But immigration fromTibet, perhaps

a millennium or so ago, largely overwhelmed the culture of the Dards and obliterated

their racial characteristics. In eastern and central Ladakh, today's population

seems to be mostly of Tibetan origin. Further west, in and arond Kargil, there

ismuch in the people's appearance that suggests a mixed origin. The exception

to this generalizationis the Arghons, a community of Muslims in Leh, the descendants

of marriages between local women and Kashmiri or Central Asian merchants.

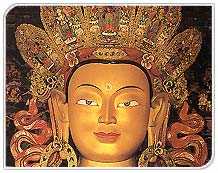

Buddhism reached Tibet from India via Loadkah, and there are ancient Buddhist rock engravings all over the ragion, even in areas like Dras and the lower Suru Valley which today are inhabited by an exclusively Muslim population. The divide between Muslim, and Buddhis Ladakh passes through Mulbekh (on the Kargil-Leh road) and between the villages of Parkachick and Rangdum in the Suru Valley, though there are pockets of Muslim population further east, in Padum (Zanskar), in Nubra Valley and in and around Leh. The approach to Buddhist village is invariable marked by mani walls which are long chest-high structures faced with engraved stones bearing the mantrra im mane padme hum and by chorten, commemorative cairns, like stone pepper-pots. Many villagers are crowned with a gompa or monastery which may be anything from an imposing complex of temples, prayer halls and monks dwellings, to a tiny hermitage housing a single image and home to solitary lama.

Islam too came from the west. A peaceful penetrationof the Shia sect spearheaded by missionaries, its success was guaranteed by the early conversion of the sub-rulers of Dras, Kargil and the Suru Valley. In these areas, mani walls and chorten are placed by mosques, oftern small unpretentious buildings, or Imambaras imposing structures in the Islamic style, surmounted by domes of sheet metal that gleam cheerfully in the sun.

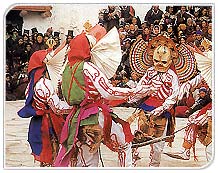

The demeanour of the people is affected by their religion, especially among the women. Among the Buddhists, as also the Muslims of the Leh area, women not noly work inthe house and field, but also do business and interact freely with men other thatn their own relations. In Kargil and its adjoining regions on the other hand, it is only in the last few years that women are emerging from semi-seclusion and taking jobs other than traditional ones like farming and house -keeping. The natureal joie-de-vivre of the Ladakhis is given free rein by the ancient traditions of the region. Monastic and other religious festivals, many of which fall in winter, provide the excuse for convivial gatherings. Summer pastimes all over the region are archery and polo. Among the Buddhists, these often develop into open-air parties accompanied by dance and song, at which chang, the local brew made from fermented barley, flows freely.

Of the secular culture, the most important element is the rich oral leterature ofsongs and poems for every occasion, as well as local versions of the Kesar Saga, the Tibetan national epic. Buddhists and Muslims. In fact,the most highly developed versions of the Kesar Saga,a nd some of the most exuberant and lyrical songs are said tobe found in Shakar-Chigtan, an area of the western Kargil district exclusively inhabited by Muslims, unfortunately not freely open to tourists yet. Ceremonial and public events are accompanied by the characteristic music of surna and daman (oboe and drum), originally introduced into Ladakh from Muslim Baltistan, but now played only by Buddhist musicians known as Mons.

Ladakh Home »

About Ladakh Travel

Guide » Religion

& Culture » Historical

Background » Ancient

Routes » Modern

Routes

Central Ladakh » Fairs & Festivals » Oracles & Astrologers » Arts & Crafts » Cultural Tourism » Archery & Polo » Adventure in Ladakh

The New Areas » Tourist Information » Air Line Ticketing » Car Coach Rentals In Ladakh

Travel Agents & Tour Operators in Ladakh » Hotels & Resorts in Ladakh » Map »Travellers Tools

Central Ladakh » Fairs & Festivals » Oracles & Astrologers » Arts & Crafts » Cultural Tourism » Archery & Polo » Adventure in Ladakh

The New Areas » Tourist Information » Air Line Ticketing » Car Coach Rentals In Ladakh

Travel Agents & Tour Operators in Ladakh » Hotels & Resorts in Ladakh » Map »Travellers Tools