|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| About

eIndiaTourism.com |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| About

eIndiaTourism.com |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

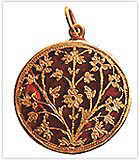

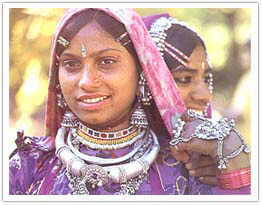

and

rings. With the advent of the Mughal Empire, Rajasthan became a major

centre for production of the finest kind of jewellery. It was a true blend

of the Mughal with the Rajasthani craftsmanship.

and

rings. With the advent of the Mughal Empire, Rajasthan became a major

centre for production of the finest kind of jewellery. It was a true blend

of the Mughal with the Rajasthani craftsmanship.  The

article is then left in the oven on a mica plate to keep it off the fire.

Colours are applied in order of their hardness those requiring more later

when set it is rubbed gently with the file and cleaned with lemon or

tamarind. The craftsmen in Jaipur are believed to have originally come

from Lahore. In Jaipur the traditional Mughal colours of red, green and

white are most commonly used in enameling.

The

article is then left in the oven on a mica plate to keep it off the fire.

Colours are applied in order of their hardness those requiring more later

when set it is rubbed gently with the file and cleaned with lemon or

tamarind. The craftsmen in Jaipur are believed to have originally come

from Lahore. In Jaipur the traditional Mughal colours of red, green and

white are most commonly used in enameling. stone

is pushed into the Kundan. More Kundan is applied around the edges to

strengthen the setting and give it a neat appearance. This was the only

form of setting for stones in gold until claw settings were introduced

under the influence under the influence of western jewellery in the

nineteenth century.

stone

is pushed into the Kundan. More Kundan is applied around the edges to

strengthen the setting and give it a neat appearance. This was the only

form of setting for stones in gold until claw settings were introduced

under the influence under the influence of western jewellery in the

nineteenth century.